|

Neville Gabie Experiments

in Black and White |

|

|

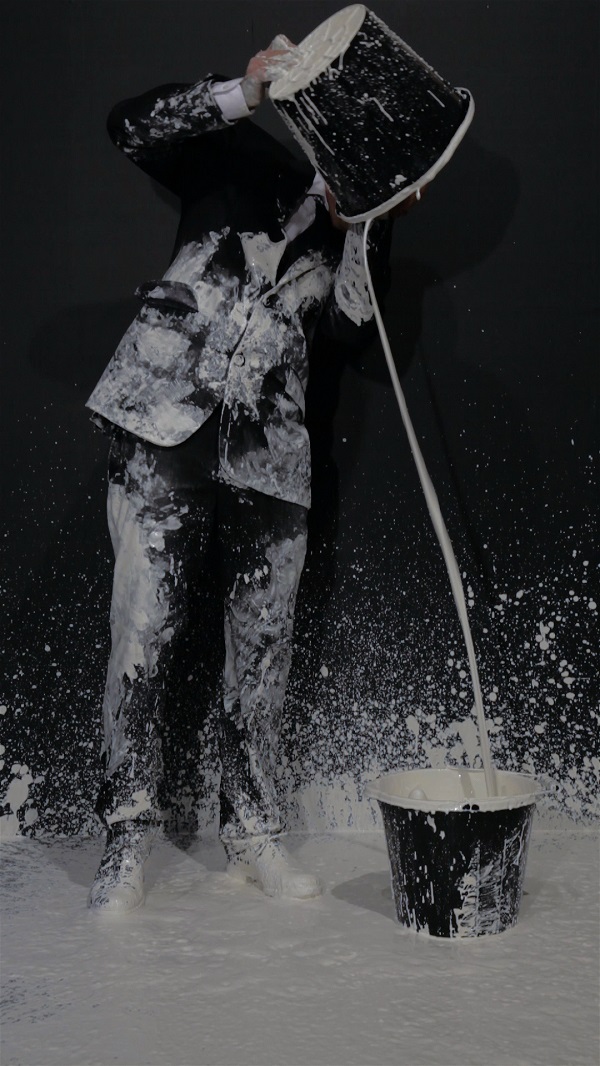

Neville Gabie Experiments in Black and White IX - liquid chalk 2012 video still |

|

Tessa Jackston Experiments in Black and White |

|

This exhibition reflects some of the more private aspects of Neville Gabie’s artistic practice. Well-known for the work he makes in relation to public sites and contexts such as Cabot Circus in Bristol (2006-09), the Olympic Park in London (2010-12) and Achiltibuie in North West Scotland (2012-14), this selection comes from Gabie’s continuing deliberations, personal deliberations, on how an artist reviews and responds to issues that surround us. Experiments in Black and White is an on-going series of works, started in 2012/13 that the artist adds to occasionally. It is only the second time that much of this work has been shown, as Gabie is not by natural inclination a ‘gallery’ artist and usually his work is presented or experienced outside such a context. The phrase ‘socially engaged practice’ attracts so many assumptions and in considering Gabie’s work it falls short. As an approach it suggests working collaboratively with people, with communities, which he often does. It sometimes refers to encouraging people to participate in social interaction and collective activity, and again Gabie has worked in this way. Yet as much as the final trace, the process of devising is of equal importance for him. At Cabot Circus he brought together construction workers and a local choir to give a concert in the concrete structure of a half-built shopping centre; he inserted stone, carved in China and personally transported overland, into the physical fabric of the site; at the end of the three-year residency he compiled a building site cookbook of workers’ recipes, reflecting over fifty nationalities and the many skilled trades that had been brought together to form a new commercial centre in the city. Spending time in a particular context, beginning to understand who or what its community might be, is the journey Neville Gabie regularly undertakes. At Cabot Circus he realised that construction sites are not necessarily about buildings but about people. He rarely undertakes projects knowing exactly what he intends to do. Experiments in Black and White began in a similar way. In 2012 he was invited to spend a year with the Cabot Institute, the University of Bristol’s cross-disciplinary centre, that conducts world-leading research on ‘the challenges arising from how we live with, depend on and affect our planet’. Focusing upon major issues at the centre of ‘the human-planetary relationship’, such as food, water and environmental change, the Institute brings together academics from a wide range of disciplines in the hope of catalysing ‘new, potentially radical ideas’ and solutions. Gabie found himself engaging with glaciologists, social scientists, vulcanologists and other specialists by establishing ‘a common room’. It became a conceptual space where he invited everyone to bring something to the table from their own specific area of interest. It had to be something which was at the gravitational centre of their research. It could be an object, a concept, an equation, an image… From this intellectually stimulating context he developed, along with a separate collaborative project entitled Archiving Oil, a series of personal studio based films that consider three materials – oil, chalk and glacier ice. Experiments in Black and White had begun but, as with research, the experiments were never going to fit into any specific time frame. Working in the rock store basement and getting into illuminating conversations, Gabie started to consider materials in a new way. Originally trained as a sculptor, materiality and possible manipulation had always intrigued him. Here he was finding out about materials and mutability from very different perspectives. Experiments in Black White VII (2012/2017, 33.03 mins) is both a performance and a final work. In the performance the artist, dressed in a black suit and white shirt, takes a large boulder of chalk and scrapes it methodically and repeatedly along a black wall. His actions are laboured from the weight and unwieldiness of the chalk fragment. The work is made up of repetitive actions and cracking sounds. Progressively he becomes coated in chalk. The resultant drawn lines seem to form waves of water rather than rock strata. The chalk drawing left in the gallery, surrounded by small chips of sedimentary carbonate rock and his suit, becomes quiet reflections on manual labour, the nature of the material, the role of the artist and a curious sense of time. In addition, for many of us over a certain age, there are memories of school, the sound of chalk on blackboard, the process of learning and early mark-making. The work may have been in some way shaped by collaborative discussion at the Cabot Institute, but the idea and then the making of the work, albeit in front of an audience, is more solitary. Gabie’s Experiments are ways of thinking through new information, of considering aspects of society and making work in direct relation to on-going thought processes. For some time previously he had been preoccupied with the nature of manual labour, how it is perceived and understood, and how we respond to it. All his Experiments to date have involved direct actions. They offer physical ritual in relation to intellectual thought processes. Neville Gabie found his time in the Institute energising: I spent some time with staff in the Department of Mathematics. One professor I spoke to talked about his ongoing research to ‘measure and define infinity’. That whole conceit struck me as being as close to the elusive nature of art itself as anything else. Watching him work was also a revelation. He worked on three large blackboards with chalk and a duster, writing and rubbing out a whole series of equations, moving from one to the other with such speed and intensity, that the whole experience required great physical exertion. He was engaged in what is perhaps the frontline of pure maths, but working with one of the most ancient of natural materials, chalk, and in doing so particles, many millennia old, were being broken to dust as they fell to the floor. When he had finished I was curious to know why he worked in what seemed like a basic way with chalk and board. Why not a computer? His answer itself made such sense in relation to my own practice. What he talked about was the relationship between the hand taking a physical action and the speed and way in which the brain, his brain, could process his thoughts. The understanding and the processing of thought through action is exactly the point at which our work intersects. Here, facing the chalk drawing, is a small monitor on the floor showing a work called Experiments with Bideford Black V (2015, 3.35 mins). Commissioned by Flow Projects and Burton Art Gallery, Devon, the artist collaborated with fellow artist Joan Gabie and social geographer Ian Cook, to develop new work in response to the naturally occurring pigment Bideford Black. Mined in the area until cheaper chemically produced ‘blacks’ took over, the soft clay-like material runs alongside seams of high quality coal. ‘Mineral Black’, or ‘Biddiblack’ was produced commercially for the boat building industry, for colouring rubber products and was even bought by Max Factor to make mascara. In this video Gabie, in black suit and covered in the pigment, walks into the sea. The varying grey tones of shingle beach, waves and deeper water offers a cold dispassionate environment. As he walks the pigment mixes with the water, colouring it and suffusing with it. In some ways it is a modest work, displayed small and at one’s feet, yet it is curiously affecting. The monochromatic scene prompts thoughts on the physical nature of pigments, their extraordinary density and opacity, how they are used and controlled by artists, how society uses its minerals, how materials that are millennia old are dispersed and expended. Experiments with Bideford Black V provides an appropriate counter-part to the chalk drawing opposite. Throughout Neville Gabie’s work, both private and public, the importance of place is ever present. The reference to place is specific and particular. The walk into the sea took place opposite a vertical seam of Bideford Black on the Devon coast. Experiment in Black and White XXII (Royal Realm), (2017, 64.33 mins), was made for a recent project where three artists reflected on the relevance today of Robert Tressell’s novel The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists. Well known for its central premise of ‘the fundamental need to replace the entire capitalist system with a new and more radical society’ (Tony Benn, 2012), the classic text of ‘working class literature’ generated work that was then presented at Croxteth Hall, north of Liverpool. The Hall was the home of the final Earl and the Countess of Sefton and as a set of interiors, it reaffirms the status of life above and below stairs. Gabie’s video of just over an hour follows a man dressed in a dark suit painting himself and the backdrop behind, with white household paint. The work, originally shown alongside portraits of the aristocracy, appeared almost humorous yet jolted the visitor into realising who had been erased from the stories that are told at Croxteth Hall today. Its title is taken from one of the building’s grander paintings and the video plays upon both the portrait painter and his sitter by the action of literally painting out an individual. In doing so Gabie alludes to the anonymity and lack of acknowledgement paid to servants who worked to sustain the life-style of those who are named and are still referred to today. Here, in quite a different setting, the work connects to his other Experiments, by maintaining the associations of repetitive labour and ritual, but the viewer once again can play with the notion of what has become obscured and what is made visible. Experiments in Black and White XIX (2016, 2.32 mins), another video, shows a man holding a large pile of plates, who after minutes of trying precariously to bear their weight, drops them. The inevitable crash circulates around the house, disrupting the space, before the work is even seen. Made on a residency in a former steel blast-furnace complex in Belval, Luxembourg, the action took place in a site where enormous industrial structures have been preserved and restored. Here, Gabie’s endeavour connects more to the domestic feel of the house in which the gallery operates. The building is both a home and a set of gallery spaces; its interiors are Georgian in scale as well as architectural detail. When considering the selection of work for this exhibition, there was discussion of the domestic sensibility of the spaces. On first entering the building, One Hundred Pieces (1999/2000) sets the scene. Images of found domestic objects line the walls - the discarded items were collected by the artist during a residency in Liverpool. Dragging them back to his temporary studio, he was at pains to document them, almost like a diary of his walks across the city. He made other works that were intensely public in collaboration with the local community and other artists but these have always formed a framework for personal deliberation. It is evident that Neville Gabie needs to make these more personal works to process what he comes across during his public interactions with people and their situations. Starting out as a maker of objects, he became a constructor of projects that interact with the wider world. He has spoken of how he grew up as an artist concurrently with the YBA set (Hirst, Emin, et al.). As the artworld became more openly commercial, Gabie’s work in contrast became less determined by the market place, and connected more to what he experienced in everyday life. He found purpose and relevance in engaging with workers on construction sites, such as the Olympic Park; he continues to enjoy connecting with people. Yet Hours of Darkness (Stroud), (2016) and Hours of Darkness (Eynhallow), (2017) are perhaps the most personal works here. The artist set himself the task of drawing throughout the hours of darkness from the onset of a winter’s night till dawn. In the second work he drew again during the hours of darkness, but in Orkney in May there is more light than dark. In both works he started precisely when the sun set and stopped when it rose over the horizon – they make explicit his capacity to continue to draw. The fading in and out of density, in blackness and in line, is derived from starting and exhausting marker-pens through this meditative labour. Gabie often includes the measuring of time through the making of work. He remains a maker and a craftsman and considers how this role is seen today. As someone who has always been self-effacing in approach and in encouraging others to share what for them is their ‘gravitational centre’, he is ambivalent about showing a sense of his own self in his works. However, these very works support his public practice. It is his Experiments in Black and White, along with a small number of other more private works, that enable him to unpick subjects, debate issues and then respond with such clarity when collaborating. They are integral to his ethos that artists should involve themselves in contemporary society and, through their work, be politically active. Tessa Jackson OBE is an independent curator, writer and cultural advisor. She first worked with Neville Gabie in the 1990s. They are currently developing a larger exhibition project which is planned for 2019/20. This text had been written on the occasion of the exhibition Experiments in Black and White curated by Tessa Jackson. |

| >home |