|

Assunta Abdel Azim Mohamed |

|

|

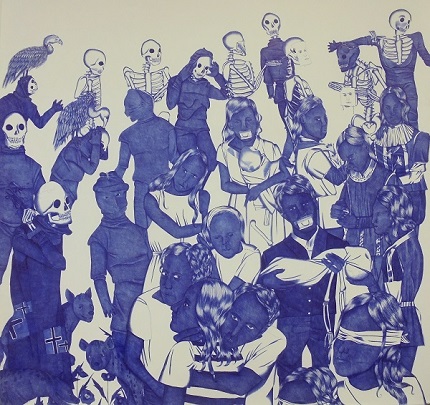

Assnunta Abdel Azim Mohamed Imposters 2017 ballpoint pen on paper 100 x 100 cm |

|

David Lillington Assunta Abdel Azim Mohamed |

|

In 2015, in a brief catalogue entry for a group exhibition, Assunta Abdel Azim Mohamed wrote of how as a child her mother told her her drawings contained too much white space, and that she should fill it in. ‘Ever since, I have taken her advice to heart with every drawing I do.’ It’s a way of parodying herself, of course, of joking about her evident horror vacui. But it is interesting to see how formal an approach to her own work she takes, reflecting on the nature of the drawings as drawings. The importance of their figurative nature and elements is obvious. But perhaps these two aspects of the work are in harmony – and this leads me to the following thought. According to recent (especially German-speaking) scholars, the Death and the Maiden motif (as it exists in its early form, from roughly 1510 to 1550, in paintings, prints and drawings) has an ‘art-about-art’ aspect. Its content, its effects, they say, rely on its play with gazes, on its provocations, on ideas about unveiling, nakedness and being clothed, about time, on its use of mirrors and other art-related motifs. These kinds of aspects of art history are things Mohamed picks up, and her own art, also aware of art’s self-awareness since Modernism started out in the 19th century, is to a great extent an art about art. Jean Wirth in the first major study of Death and the Maiden – La Jeune Fille et la Mort of 1979, says that the Baroque revival of Dance of Death and Death and the Maiden imagery (and related genres) stripped out the belief from these genres. ‘Lorsque le macabre trouve dans la poétique baroque un nouvel essor, il est désormais séparé de la croyance.’ It left, he says, a decorative Catholic imagery à bon marché: cheap. Mohamed grew up in a Catholic country, and in school came across this death imagery through a study of the Baroque. As someone who was already making complex, more or less funny drawings, the appeal is obvious. She wrote to me that ‘in Baroque Carpe Diem, Memento Mori and Vanitas imagery I saw parallels in the contemporary art world.’ There are some clues here to ‘explaining’ Mohamed’s work. Her study continued through Symbolist literature and 20th century art to the work of her contemporaries. She started out as a student of Romance Studies, then signed up for print and illustration. Having an understanding of the artists she admired, she knew that what she was doing was fine art. In using the ‘cheap’ style of a decorative Baroque death imagery for a satire of the society around her, she brought to this style seriousness and new content and possibly – in the absence of any real ‘belief’ properly speaking – a kind of belief. Her drawings have wit and obvious elements of caricature but they are also meditations on life and its relationship with death. It is not necessary to understand all the details in Mohamed’s drawings. You might be forgiven for thinking that she doesn’t understand them herself, since in the short ‘Erklärungen’ (explanatory notes or clarifications) which she has written for her Austrian gallery (Ernst Hilger) she often says ‘it seems as if...’ or ‘perhaps he or she is doing such and such...’ as if to suggest she drew the pictures and thought about the meanings later. It is not so simple. But the thought leads to a truth about the work. Naturally there are keys to things: the woman in the coffin in We all want to party when the funeral ends (2015, not in this show), the artist tells me, has just woken up, as if from a nightmare, to realise she is mortal and will die. The clothes worn by the skeleton coffin-bearers are based on those Mohamed saw in the Vienna Funeral Museum. The other characters around the procession are mourners - come rather too early, since the woman is still alive and not under immediate threat. Necrophilia is so 1846 refers to a famous legal case; the man in Enjoying a healthy life is drugging or poisoning the woman’s drink. The Ancient Egyptian images on the shirt in I am not old enough to die for your mistakes are allusions to death rites, the plants in the background are the poisonous hogweed. And so on. But Mohamed has learnt the lessons of Symbolism, in which the idea was that images not only carry very broad references but take us into another world, where other realities are found. Her images are not allegorical, it is not a case of this-means-this, this-stands-for-this. She is on a journey through the areas of culture which interest her and a journey through the inner life of contemporary Vienna. The cultural areas range from Baroque style in general, including its decorative death imagery, and certain Baroque artists in particular, including Velazquez and Caravaggio, to contemporary music and music video (many of her titles are lines from songs). Writers and artists we discuss include Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Lautréamont, E. T. A. Hoffmann, Frida Kahlo, Christian Schad. Among the living: Muntean and Rosenblum, Jerome Zonder, Suehiro Maruo, Njideka Akunyili-Crosby. Going back to the details: in her notes she writes, ‘perhaps the cuts in her arm have something to do with the plants behind her’ – or perhaps not: as if she were playing with our wish to pin everything down. Or, as if she didn’t know herself the truth about these cuts. The cuts her characters exhibit are self-inflicted, inflicted by others, or might be either or both. There is a psychological truth in this. In life, who is responsible for what is not always clear. And to return to technique: the cuts seems to have something to do with the making of marks on paper, the skin – with its cuts and tattoos and words – with the drawing technique. There is an interest in surfaces, a connection between this and the things she draws: not just skin and clothing but flowers and insects and entrails, in the pieces which mix those. And there is hardly an inch that does not allude to some cultural knowledge, high or low. Jean Wirth elsewhere in his book complains that the followers of Hans Baldung Grien lost the hardness of his early Death and the Maiden paintings. This softening of the imagery after its original shocking inception in his work, he regards as decadent and lacking in intellectual and psychological rigour. It pleases, it no longer shocks. Mohamed re-introduces shock, using a kind of magic social realism. The true subject of her work is people. Baldung, as it happens, and however absurd the comparison of the two artists might seem, does prove a useful point of reference. Both are interested in psychological extremes, and in trying to describe them; both are fascinated by how this relates to the nature of art itself. Their pictures talk about themselves to the viewer. They want to address both art and life. Hence my description of Mohamed’s drawings as ‘tattoos’ – they have a desire to be living, or to be somehow inscribed on life itself. One might add as an aside, both of them show an ‘unhealthy interest’ in mortality because they live in times in which war and social upheaval threaten. Wirth’s analysis of Baldung’s personality reveals him to have been very much like a Surrealist. Mohamed is explicit about her interest in Surrealism (the heir of Symbolism), though her description of her characters as being in ‘surreal situations’ may be a way of not having to explain each detail as if it were allegorical (even when a thing does allude to something else). This combination of definite and indefinite appears when people are art’s subject. Mortality is not simple; nor should its depiction in art be. And one does not simply embrace death. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross, psychiatrist author of the famous and much argued over On Death and Dying, made that fact clear at least. We negotiate with it. What Mohamed is working on is something like a literary narrative work, a complex art, and one that ignores the distinctions between art and literature. It is a party we are at in her drawings, a wedding party in the graveyard or a wake at a wedding, a music video rendered in biro with ‘symbols from different realms, distilled and assembled into a dense pictorial language’, as she says. The ‘symbols’ are attributes and observations and allusions, in these frieze-formatted Dance of Death tragi-comedies, these still-lifes of entrails and flowers, which are at once old-fashioned and 21st century. Her hand-crafted works are meditations on people’s lives and on art itself, and it is a kind of meditation which seems as haptic as it is visual. David Lillingtonis a writer and curator based in London. He is a member of the Association for the Study of Death and Society and of the International Association of Art Critics. In May 2017 he presented Mohamed’s work at the conference Death and the Maiden, University of Social Sciences, Łódź, Poland. . This text had been written on the occasion of the exhibition Assunta Abdel Azim Mohamed curated by David Lillington. |

| >home |