| Abraham Kritzman and Eyal Sasson Stand Still |

|

|

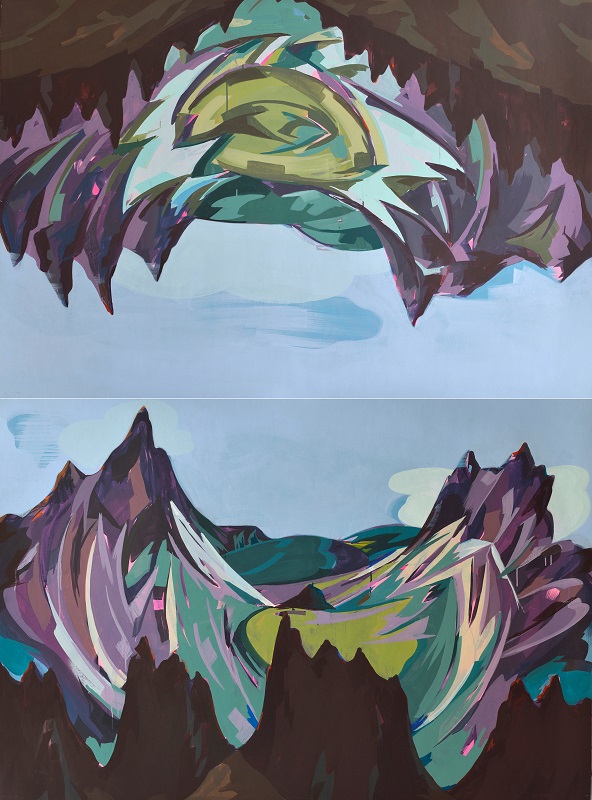

Eyal Sasson Untitled 1 2017 acrylic on paper 214 x 157 cm |

|

Keren Goldberg Stand Still |

|

At first sight, Eyal Sasson and Abraham Kritzman seem to draw from completely different aesthetics and subject matters: Kritzman’s woodcut prints, pedestal-like plaster sculptures, graphite drawings and diluted oil diptychs, are all saturated in an austere, dark palette of murky colours. They stand in direct contrast to Sasson’s bright coloured, graphic, even child-like marker paintings and three-dimensional paper-cut pop-ups, all depicting hallucinatory landscapes or upside-down worlds. It is thus surprising to discover that both painters embark on their creative journeys from a similar departure point: walking voyages. Sasson has been walking through many areas in Israel, Jordan, Santiago, Spain and the Dolomites, Italy; while Kritzman has been walking pilgrimages and stretches of land in Santiago, Spain; Shikoku, Japan; Canterbury, England and Piatra Neamt, Romania. The act of walking here is not that of nationalistic or romantic nature, but is more in line with its ancient Greek meaning: in Aristotle’s Peripatetic School, the great philosopher used to teach while walking together with his students (the name of the school derives from the Greek word ‘peripatêtikos’, meaning ‘of walking’). Aristotle believed that walking grants the thought flexibility and fluidity. Sasson and Kritzman’s walks are means for encounters. Rather than the traditional model of immobile outdoor painting through observation, they gather their experiences in motion. This in turn affects the way elements such as perspective, horizon and focal points are later translated in their works. Moreover, the two painters’ in-motion gathering process cannot be separated from their studio work, and from the subsequent process of encountering their work. In their walks, both artists encounter, first and for most, nature. According to Aristotle, nature includes all that possesses the principle of motion and repose, meaning – all that is inherently in-movement, including the human-being (1) – or in our case, the artists. Nature is that of ceaseless change, but it also persists despite changing conditions, much like the painter-walker, who attempts to capture its fleeting encounters in a stand still object. ‘Landscape is not a genre of art but a medium’, writes W.J.T. Mitchell in his seminal Landscape and Power (2). Sasson’s usage of landscape follows this declaration. However, more than exploring landscape as an instrument of cultural power, the painter is much more interested in landscape as a platform for painterly manipulations and experiments: in his previous works, he created reversed outdoor drawings through Camera Obscura devices, decomposed and digitised forests to their respective red, green and blue (RGB) pixels, and used the format of ‘black mirror’ to depict nocturnal sceneries. Thus, we might refer to his current colourful pop-ups as the result of another experiment. These crafted, naturalistic dioramas follow comic-like aesthetics, inspired by mid 20th Century American graphics. Through these artificial cultural filters, Sasson translates a landscape into a graphic icon, or an ideal nature. His landscape becomes a scenery, a set. And indeed, these works evolved from painting models – Sasson would cut out elements from various photographs that he has taken en route, and combine them into a three-dimensional architectural-like model, only to later paint it. Gradually, the three-dimensionality persists, and serves to create not just a spatial amalgamation, but a temporal one as well. The elaborated act of continuous walking is cut and pasted here into a single image, or gaze. Thus, Sasson’s landscapes, in line with Mitchell’s proposal, (3) transform from an object into an action, from a noun into a verb – it is a work of ‘landscaping’, not in the word’s original sense of designing landscape, but rather as working through a landscape. Sasson’s other large paintings follow a similar logic. Resembling round panoramas, they intermingle earth and sky, while referring to ancient optic perceptions of the universe. They continue Sasson’s interest in anamorphosis and his previous use of Camera Obscura, which in a sense distorts the romantic notion of painting en plein air. When using Camera Obscura, the painter enters a black box, seeing the world through its lens in a deformed manner. These paintings also develop the artist’s interest in the depths of caves and enclaves. The gaze is directed outwards, as if from inside a cave – a toothed mouth, threatening to close and obscure the light of day. While Sasson concatenates temporal encounters into three-dimensions, Kritzman flattens these into painterly platforms. His recent paintings are flat, almost textile-like in nature, becoming a staging for imageries. Some of these imageries derive from the artist’s interest in the religious aspect of walks such as pilgrimages. However, he is less interested in the religious aura of these journeys and their purpose, but rather in the materiality of the religious objects they revolve around, and the formality of the movements they summon. He often uses devices such as duplication, zooming-in or abstraction in order to transform the religious holiness into a mechanic gesture. Many works appear in diptychs – a traditional religious form. But the pair format is not used here for the creation of narrative, but rather for duplication. Two large arched drawings are reminiscent of a church-like apsis, but instead of opening up a space for a figurative sacred image, they reflect nature – a kind of pictorial thicket, made of layers of different intensity and density. The graphite lines close off the view, while constantly escaping the viewer and shimmer away. Images continue to escape the viewer in Kritzman’s round oil on steel paintings, and his woodcut prints. The fine engraved lines, hardly visible, are drawings based on various Romanian folk tales, and function as faded cultural relics. The weirdly geometric-shaped prints also bear a kind of monolithic mysteriousness or aura, which is quickly lost through the replicating nature of print-making. Here, Kritzman’s flattening act is taken into extreme – the print, as a medium, annihilates the production process; one cannot tell which line was placed first, unlike a painting, which cannot obscure the traces of its layering incarnation. All this seems to stand in direct contrast to Sasson’s volumetric pop-ups. Any human presence seems diminished in the show: in Sasson’s works, the human body is presented as a staffage, a decorative place holder or an indicator of scale, much like in architectural drawings. In Kritzman’s work, the human subject is reduced to minor traces of creation gestures, as imprinted in his plaster-casted sculptures which resemble strange fossils or non-functional objects. However, the gaze of the walking-encountering body is in the heart of the work of these two painters. In his walks, Kritzman tries to linger, to lose his way, to simultaneously gaze into the horizon and lower his sight to the ground – to become multi-focal. This kind of gaze is also present while encountering his works, which cannot be distilled into a specific linear or rational historic narrative, or alternatively – into a central perspective. The same occurs in Sasson’s circular landscapes – once earth and sky are one, there is no horizon or focal point to hang on to. In her essay In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment, Hito Steyerl described a loss of horizon, that which happens in today’s dominant vertical perspectives such as Google Maps and drones’ views. (4) ‘A horizon is a device to suggest stability in an unstable situation’, such as historic maritime navigation in which bodily gestures were used as indicators of distances, Steyerl explains. (5) But in today’s fragmented world, ‘instead of floating, many of us might be in continuous free fall, in a condition where we no longer know whether we are subjects or objects, and extreme acceleration turns into a condition of stillness and stasis’. (6) Here returns the Aristotelian paradox of nature, which persists through continuous change. In free fall, much like in the works of these two painters, ‘perspective is twisted, and multiplied. New types of visuality arise (…) As if history and time had ended and you couldn’t even remember that time ever moved on’. (7) One must remember that Aristotle’s habit of teaching through walking also derived from political constraints – as he was not a citizen of Athens and could not own property, he and his colleagues used the grounds of the school as a mere gathering place. Today, harsh national policy brings about a precarious and unstable world, in which no land is solid enough to stand on, and no horizon is steady enough to share with others. The aesthetic experience of walking and encountering within this world becomes ever more complex, stuck between eternal stasis and everlasting free fall. Notes 1. Aristotle, Physics 2.1, 192b20–23.

Keren Goldberg (b. 1985) is an independent art writer and critic based in Tel Aviv and London. She contributes regularly to various magazines such as ArtReview, Mousse, Frieze, art-agenda, ARTnews and Art Monthly. She holds an MA in Critical Writing from the Royal College of Art, London, and is currently a PhD student at the department of Visual Cultures, Goldsmiths, London, where she is researching parafiction art. She is also the leader of an art magazine reading group in Tel Aviv. |

| >home |