| O JUN Chikanobu Ishida 14 days 119 years later |

|

|

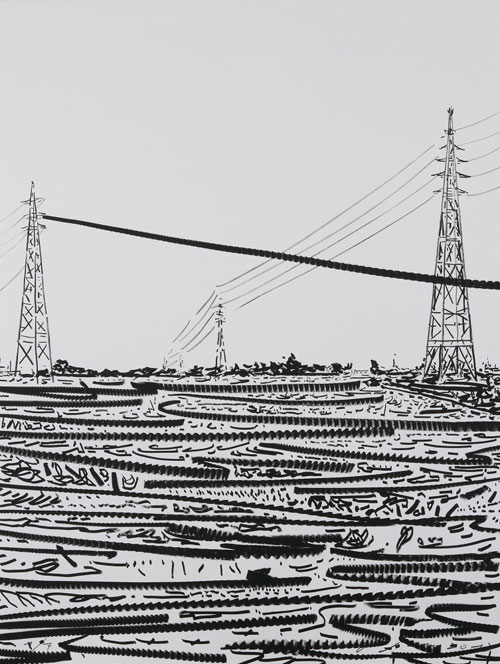

O JUN Into the river (set of 21 works) 2013 lithograph on paper

62 x 47cm |

|

Tamiko O'Brien 14 days 119 years later |

|

My daily life is not so different from that of other people, but can I really comprehend someone else’s day-to-day activities? In fact, I barely know what that would be like; I just imagine it in relation to my life. My everyday experience - that is my benchmark – but it often startles me by various small occurrences. Everything, such as my mug, the trees in a garden, a cat and even my wife, can surprise me. The world never fits naturally into me. Therefore, I find that I can only portray the temporal nature of my daily life, which startles me. 『日常について』 — O JUN, On everyday matters (2016) An assertive object drawn in heavy black ink (based on a wallpaper pattern) attaches itself to a lightly drawn girl’s skirt, as her flat cartoon arm points towards a fully rendered painting of a burning house, positioned over there, on the edge of the paper. In Japanese you have to be mindful of where the person you are talking to is when describing the location of an object or a place – it’s one of the first things you learn in evening class. Koko (here) is used for the place where the speaker is, soko (there) is the place where the listener is, and asoko (there) is used for something at a distance from both the speaker and the listener. Meanwhile the distinction between inside and outside - uchi / soto - is of particular importance: Uchi relating to home, one’s self, one’s family, the in-group of close work colleagues and the present moment; Soto referring to what is outside, to others, the out-group (possibly work colleagues in another department), otherness, foreigners, the past and the future. Where you are located in relation to the in-group and out-group will strongly influence the language you will use (1). The Japanese language is also known for differentiating between types of animate and inanimate things, through separate counting systems. Different counters are used for flat objects, for cylindrical objects, for birds, people, small animals, household appliances, and so on. Relationships exist between what might appear to come from quite distinct categories: rivers, roads, train tracks, ties, pencils and (long) telephone calls, share the same counter because they are classified as long thin things. I’ve not asked O JUN about this yet, but I have an idea

that his years of living outside of Japan gave him a

particular perspective and simultaneous understanding

of both uchi in-group and soto out-group. In O JUN’s

work, categories and details, places and things are

usually taken out of their context and new relationships

are made. Objects, people and flat design elements are

given equal importance - a pine tree and a schoolgirl

jumping, a sock, a head, a bed with the light from a

television and a mountain… It was an Autumn day in Oxford about 12 years ago, waiting for my partner to finish a phone call, I wandered into an antiquarian print shop to get out of the cold. Casually looking through the Japanese woodblock prints I came across two images that immediately and powerfully attracted me. The quarter turn gaze of the women portrayed, allowed attention to focus on the sculptural shapes of their coiffure and their elaborate hair ornaments, but there was something else that preoccupied me. Each portrait was set against a plain coloured, rectangular ground that appeared to lie on top of another picture plane. The image underneath, complete with trompe l’oeil frayed edges, holes and visible wood grain, was rather like an aged sepia photograph, representing a narrative scene with characters in action. The juxtapposition of two separate images (foreground and background) creates a space in which different moments in time and place coexist. This compositional device also informs us that we are not simply looking at a picture, but at a picture of a picture - at a picture that knows it is a picture. From a series of 50 woodblock prints titled Jidai Kagami, or Mirror of the Ages (sometimes described as Beauties of the Eras), in each print a female character represents a historical period. Hairstyles, the shaping of eyebrows, kimono fabric patterns and accessories indicate the era, with the inset images depicting scenes from daily life. The series by Chikanobu Toyohara (1838 - 1912) is considered to be the last masterwork of one of the last ukiyo-e woodblock print masters. Produced in 1897 during a turbulent period, with rapid modernisation and Western influence, they present a nostalgic view of bygone times by an artist who had also served as an active samurai warrior only 26 years earlier. The word mirror is highly significant in Japanese, carrying a spiritual and metaphysical meaning from Shintoism where the word kagami implies a relationship between deities and humans, between inner and outer worlds. Written history was referred to as kagami and I am reliably informed that the woodblocks used for printing ukiyo-e were regarded as having the status of a mirror, having a kami (Shinto deity) spirit. One print in Chikanobu’s series depicts a young woman holding a mirror while in the background image an itinerant mirror polisher is at work. During the Edo period the mirror polisher would make an annual visit to wealthy households to restore the bronze mirrors to their former shining quality. In The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat (3), the writer and neurologist Dr Oliver Sacks writes about Dr P, a musician who was suffering from visual agnosia. Dr P found it impossible to recognise what he saw even though his eyesight was good and his intellectual skills were functioning well; indeed he continued to work as a University professor. He literally mistook his wife for his hat, a doorknob for a person’s face and his own foot for his shoe. As a test, the writer handed Dr P a rose and asked him to describe it. The rose was carefully observed and Dr P described it as a ‘convoluted red form with a green attachment’. As awful as Dr P’s predicament was, impinging hugely upon his daily life, he was seeing the world about him as a succession of forms uncluttered by meaning, assumption or habit. O JUN is sat at a table with his head immersed in a helmet-like object made of cast lead. Its surface finish is rough, unformed, like something still emerging, it weighs 45 kilos. O JUN sits attentively listening and then acting upon a request from a female protagonist: ‘Today is my birthday! My son, please draw this rose for me!’. Taking 5 coloured crayons from his pencil case, O JUN, with his head encased, is unable to see and has no idea which colours he is using as he attempts to draw the red rose. Each time the wrong colour is employed he is instructed ‘No! It’s different! Once more!’. In this collaborative video work Light Ray (Kōsen), 2014, made with fellow artist Takashi Ishida, we are provided with various views of the scene. A space with a table and window where the woman stands looking in at O JUN with the rose, another view where we can see that this space is actually a temporary film set within a gallery space with an audience, where the view through the window of a tree in the distance is in fact a view through a window beyond the window. The person filming can be seen checking the focus. Chikanobu’s pictures know they are pictures, O JUN and Ishida’s video is a film that knows it is being filmed. Notes: 1. This also applies to gift giving, in An Anthropologist in Japan, Routledge, 1999, Joy Hendry describes a visit to friends at New Year with a gift of strawberries carefully and, as she thought, appropriately wrapped. She found that her companion had brought the same gift but unwrapped. In this particular situation the unwrapped gift was an expression of intimacy with the gift receiver, rather than any lack of care. 2. From O JUN 1982-2013, published by Seigensha, 2013. 3. Dr Oliver Sacks, The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat, published by Picador, 1985. |

|

Tamiko O’Brien, artist and one half of the collaborative duo Dunhill and O’Brien, curated the exhibition 14 days 119 years later. Tamiko is Principal at City & Guilds of London Art School. |

| >home |